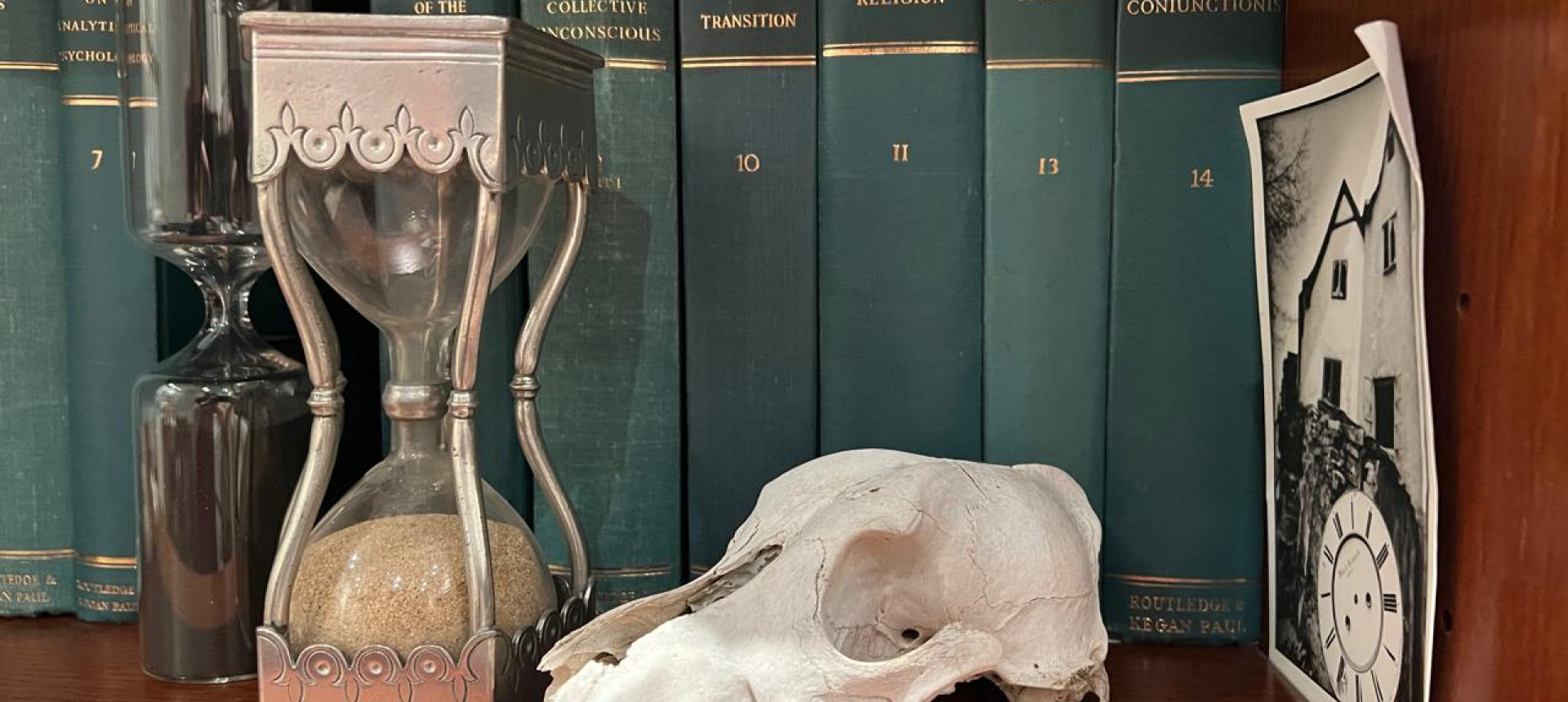

From Sensationalism to Soul: Reclaiming Meaning in the Age of Spectacle #mementomori

‘There has been terrifying accident; someone is critically injured.’ This sentence should have been enough. It’s already too much. It contains, in its brevity, everything that truly matters: vulnerability, suffering, mortality. It’s a sufficient reality check: accidents happen all the time; lives change forever; we are mortals and have no control; a life can be shattered by chance. And yet, it’s never enough.

Before the blood dries on the street and traffic resumes, a grotesque ritual begins. The masses crave for more. The images, the details, the footage, the backstory, the reactions. Strangers (many of whom claim, or even would like to think, they are not - 6 degrees of separation go a long way) swarm like scavengers. The language always laced with ‘sympathy’. Someone, somewhere is clinging to life, while elsewhere others crave for fragments of pain. And if that ‘someone who is critically injured’ does not own real-estate in your soul you could imagine this to be actual concern, a sign of the empathic collective spirit.

Let’s be blunt. There is no actual concern, and this must not be mistaken for empathy. Beneath this public, insistent ‘empathic’ need for information runs a current of hunger for horror. This is the root system of sensationalism: in a culture of spectacle, we do not ‘suffer with’, we spectate. Instead of facing death we avoid it by outsourcing it to the misfortunes of others.

And yet, the ancient whisper remains: memento mori. Remember that you must die. This musing is a meditation on what happens when that whisper is drowned out by the roar of sensationalism, and what might mean to hear it again. It is a call to pause the performance, to step out of the collective hypnosis, and to ask: What does it mean to remember the inevitability of death in an era that cannot bear to look at it?

There are two interlaced dimensions to what I’m referring to. There’s the obvious and well-explored (but underestimated) unethical media behavior. If it bleeds, it leads. Media sensationalism thrives on pain while wearing the mask of compassion. The more gruesome the image, the more it spreads. The more intimate the suffering, the more aggressively it’s consumed. What masquerades as empathy is thinly veiled voyeurism. In the context of tragedy, the crowd doesn’t mourn. It reacts. It amplifies. It sensationalizes. It doesn’t ask for the truth. It wants emotion, drama, details, immediacy.

Susan Sontag’s critique of how repeated exposure to violence and death dulls our emotional and ethical responsiveness, speaks directly to the collective condition I am describing, where sensationalism eclipses reflection and spectacle replaces depth[i]. The display of death is consumed in modern culture not as a solemn reminder of our mortality, but as an aestheticized experience stripped of moral weight and gravity. There’s a disturbing ease with which modern spectators consume suffering and death.

Behind all this — beyond the media, the gossip, the ‘thoughts and prayers,’ and the hashtags — lies a far more profound dimension. The ancient terror of humanity’s fear of death. This aspect of sensationalism is a cultural armor against our mortality and, at the same time, it exposes our collective defense mechanism against it. If we would truly remember death, our own inevitable death, we would bow our heads and fall silent in self-reflection; we wouldn’t dare reach out and ask for more. Instead, sensationalism gives us a story to chew on so to avoid at all cause to look inwards. Sensationalism is the collective acting-out of death denial: it dramatizes death in order to make it someone else’s. The stronger the acting-out, the furthest we move from our soul. Most people live in denial of death not through silence, but through excess. Excessive noise. Excessive drama. Excessive stimulation. Excessive ‘concern’. As Carl Jung observed “People would do anything, no matter how absurd, to avoid facing their own souls.”[ii] No matter how absurd… we have turned the absurd into an algorithm.

Ernest Becker, in his seminal book The Denial of Death, argued that much of human behavior is shaped by our desperate need to repress the terror of our mortality. “This is the terror: to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, and an excruciating inner yearning for life and self-expression – and with all this yet to die.”[iii] At the heart of modern culture lies a “vital lie”: that death can be avoided, outwitted, or at least kept out of view. We build systems, stories, and symbols not to honor death, but to ward it off, to buffer ourselves from the raw fact of finitude. Sensationalism is one of these buffers. It presents death at a distance, a misfortune always happening to someone else, always externalized.

We consume tragedy to locate death safely outside ourselves. The more horrific the story, the safer we feel, because it reassures us that we are not in it. An example of this is the seemingly reflective “It could have been me” that follows a tragic accident. This is an existentially ludicrous, deeply superficial and erroneous statement, that is false to its grammatical core. The verb phrase 'could have' expresses possibility in the past or an unreal past situation, i.e. a hypothetical past that implies you have in fact escaped this possibility: “Could have been, but wasn’t.” You have just misplaced mortality onto another while protecting yourself from direct contact with reality. This is a deflection, a totally incorrect phrase because, inevitably, “It will be me. It is me.” It’s far easier being horrified than honest with yourself. Sounds absurd? It sure is. Remember Jung: no matter how absurd, as long as you avoid your own soul. “This is a mirror of my mortality” would be an honest alternative, a way into your soul.

“It could have been me”. These erroneous hypothetical words are an incantation not of solidarity, but of defense. We utter them to keep death at bay, to make it about “luck”, circumstance, anything but the Truth: That we are all vulnerable, all temporary, all mortals. This recoil from our own fragility is the epitome of our existential denial. Albert Camus called death the most obvious absurdity: To live is to face the absurd, the tension between our desire for meaning and the silent indifference of the universe.[iv] But instead of reckoning with this absurdity, sensationalism makes death banal. It replaces existential confrontation with spectacle. In the face of someone’s tragic circumstance, we scroll, we consume, we crave for more details. This is not revolt, as Camus urged, it’s surrender. We do not defy the absurd. We (tragically attempt to) anesthetize it.

We collectively deny death. And this aspect of our collective shadow is currently running wild in the digital age. We don’t confront death, we project it at large, we disown it. “It wasn’t me, after all”, and the victim becomes an external vessel for our repressed fears. The media, meanwhile, becomes the high priest of the ritual, guiding us through the illusion that in watching others’ suffering and in participating in strong emotional responses, we are, somehow, purified. Our collective refusal to confront the shadow finds refuge in a world dominated by sensationalism, where tragedy becomes content. Let me be clear: We are not participating in mere cultural immaturity; this is a collective disintegration, a dangerous mass refusal to confront the shadow.

For Jung the greatest danger to humanity is not an external catastrophe, but the human unconscious: the parts of the psyche we deny, suppress, and project onto others. Sensationalism, viewed through this lens, is a projection of the collective shadow onto others’ suffering. Instead of confronting our own mortality, frailty, and fear, we outsource it. The horror is real, yet the meaning is deflected by projection. Jung warned that what we do not face within, we will encounter without, often in a distorted, monstrous forms. Sensationalism is one such monstrosity: a grotesque mirror reflecting back our inability to suffer consciously the inevitable and absurd condition of being human. Rather than integrating death into the psyche, to recognize it as a fundamental, inevitable part of being, we watch it at a distance. We make our imminent death a narrative arc that belongs to someone else, a headline, a gossip. “It couldn’t possibly have been me.” And in doing so, we sever its intimacy and depth.

But as Becker warns, this denial is not without consequence. The more we repress death, the more neurotic and violent our culture becomes (yes, it is getting worse). The shadow grows. The symbolic substitutes that offer the desired distraction (be it celebrity culture, outrage cycles, or crisis addiction) only delay the inevitable confrontation. And when that confrontation comes, it arrives without preparation, without integration, without depth, without awareness. But death will find each one of us, ready or not.

We are tragically inauthentic, to borrow Heidegger’s language, unless we are willing to embrace a way of living that acknowledges our finitude – being-toward-death.[v] We have drifted away from our essence, we have lost contact with our nature, with the certainty of our mortality. We have embraced the sensationalism’s agenda, we have, in fact, perfected it. What we fail to realize is that by stripping death of its meaning, it’s power, intimacy and reality, we disservice life and in doing so we disempower ourselves. When death is a story happening to someone else, so is life: a dishonest, shallow distortion. The shadow aspect of our unconscious isn’t contained to our death denial. It spills over to every aspect of our inauthentic life. The samples are endless: accepting suffering at work for the sake of a glorified retirement; following the culture’s agenda for our personal lives; accumulating; postponing; procrastinating… We participate in a kind of ritualized perpetual shadow-feeding: we avoid our mortality, project it onto the other so we don’t have to confront it in ourselves. “It could have been me, but it wasn’t. I have time.”

What would it take to shift this paradigm?

Rejecting sensationalism does not imply rejecting suffering and emotions. It’s precisely the opposite: it is to honor them, it is to treat them as sacred encounters. This would demand us facing our mortality not as a spectacle, but as an inevitable conclusion. “This too is part of me.” In this new paradigm, we would not watch others suffering from a distance. We would witness suffering, quietly, ethically, humanly, as a reminder of what we share and of what we must one day face ourselves. “In their suffering, I meet my own impermanence.”

Jung called for the integration of our shadow, personal and collective, that begins by acknowledging our reactions and projections. Only by integrating the shadow can we reclaim a culture worthy of the fullness of the human psyche. Fear, the primitive mechanism behind our denial, would have to be dealt with as an authentic emotional state that needs to be embraced rather that as something to be broadcasted and shared in social excitation. This would imply facing death and tragedy as a sacred encounter, as a threshold that is, as Jung indicated, as important as birth. When we can perceive the inevitability of our own death as a rite, challenging as it may be to meaning (as Camus demonstrated) then we can begin to tolerate the seemingly absurd, unbearable shadows of our unconscious, personal and collective.

This is not a utopian scenario. It is difficult, painful work, both personal and collective, and it’s the only antidote to unconscious repetition. As Jung wrote “The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside as fate.”[vi] Sensationalism is fate on autopilot. Integration of unconscious material is the reclaiming of self-awareness, depth, and inner freedom from the constrains of ‘fate.’ By honoring the dark and tragic, rather than denying them, we give meaning to the entirety of our human experience. According to this paradigm death is not an event observed, nor an experience happening to someone else. It’s a defining structure of being. A certainty. It is an upcoming inescapable reality that must be embraced. “It will, for sure, be me.” As Jung indicated “If viewed correctly in the psychological sense, death, indeed, is not an end but a goal, and therefore life for death begins as soon as the meridian is passed.”[vii]

This is a call to hold mortality in minds at all times. To mourn without sharing; to grieve without explaining; to feel without performing. True grief is quiet, deep, silent, introspective. It seeks to intergrade the pain. It bears witness without performing or appropriating. It’s an inward process that begins with the individual’s honest engagement with suffering and, if embraced collectively, can lead to cultural healing. “This suffering is not theirs alone, it belongs to all of us.”

Memento mori is not a morbid position, but an urgent one, the only responsible and self-respectful way of living that honors our fleeting existence. It is a transformative existential position that demands honesty and self-awareness, two of the rarest characteristics of modern humans. Memento mori can be a call to wakefulness to an existentially clarifying life. “Their suffering is within the human condition to which I belong.”

Quietly meditating on the gravity of one’s own death is the only honest position against sensationalism’s distractions. In a profoundly shallow and self-destructive culture that feeds on borrowed pain and sustains hallow lives devoid of meaning and connection, each one of us must hold up the mirror and let our own certain upcoming death be a soul-orienting truth. This is the dignity of the finite and the beginning of authenticity. To contemplate death is not to flee from life. It is to finally arrive in life, stripped of illusions, awaken to meaning.

For N.

[i] Sontag, S. (2004) Regarding the Pain of Others. Picador

Sontag is primarily concerned with the desensitization brought about by the proliferation of violent/ disturbing images, yet her insights align with the broader themes I’m exploring. Sontag challenges the viewer of violent images to ask whether looking at suffering leads to deeper awareness or merely reinforces detachment and apathy. Her work suggests that repeated exposure to death in media inoculates us against the reality of our own finitude.

[ii] Jung, C.G. (1944). Psychology and Alchemy, CW 12: para 126.

And Jung continues: “…all because they cannot get on with themselves and have not the slightest faith that anything useful could ever come out of their own souls. Thus, the soul has gradually been turned into a Nazareth from which nothing good can come.”

[iii] Becker, E. (1973) The Denial of Death. The Free Press: page 87

[iv] Camus, A. They Myth of Sisyphus (1955). Hamish Hamilton, London.

[v] Heidegger, Being and Time (1962). Harper, New York.

[vi] Jung (1951) Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. CW 9II: para 126

[vii] Jung, C.G. (1929) Alchemical Studies: Commentary on ‘The Secret of the Golden Flower’, CW 13, para 68