Called or Uncalled: Jung’s Doorway to the Numinous

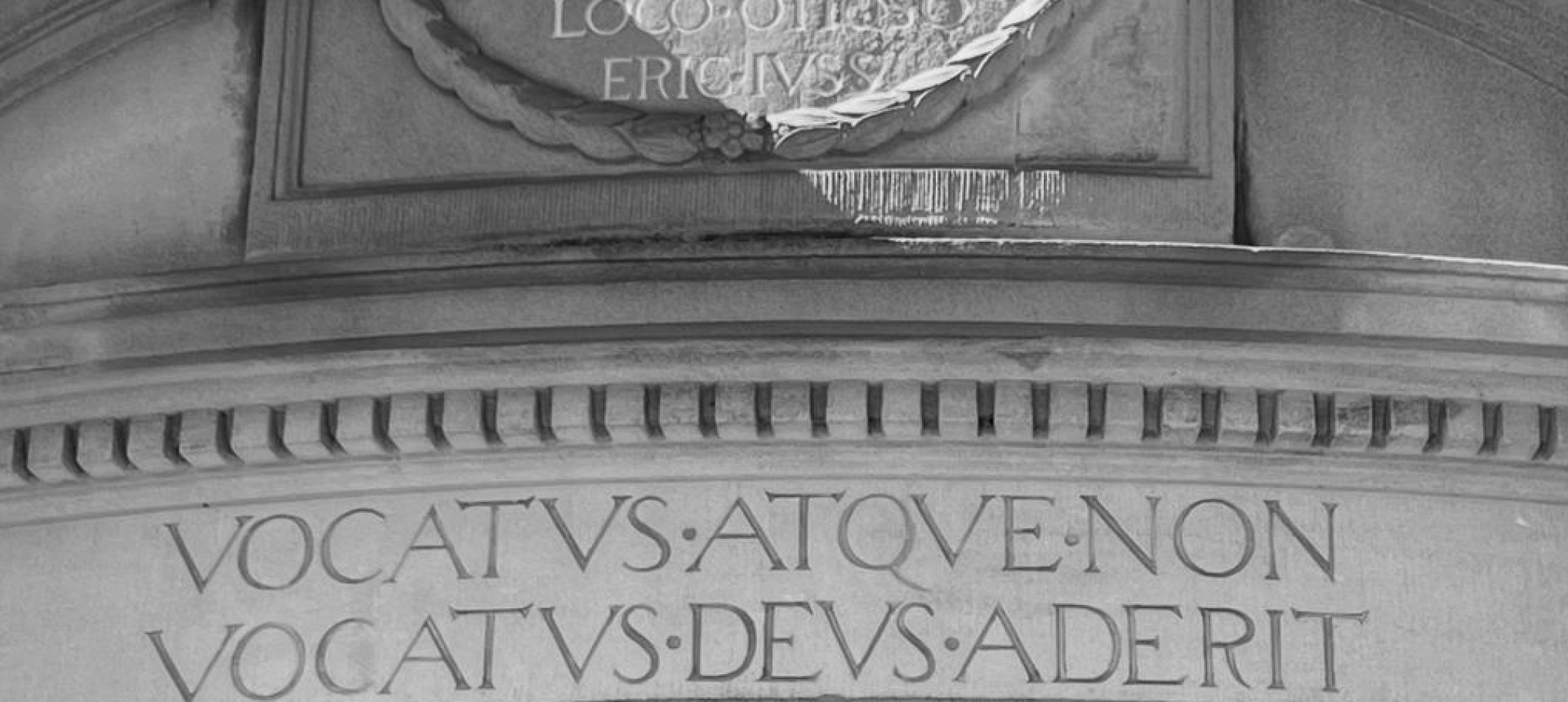

Over the main doorway of Carl Gustav Jung’s house in Küsnacht, on Lake Zurich (built in 1908), as well as on his gravestone, there stands the Latin inscription: “Vocatus atque non vocatus deus aderit.” Called or not called, God will be present.

This phrase clearly resonated with Jung; you do not carve words into stone on your doorstep and your grave unless they are existentially decisive. The line comes from the 16th-century humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam. In his Adagia (first published 1500, expanded repeatedly until 1536), Erasmus glossed an older Delphic oracle that, when consulted by the Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus, replied: “The god will be present whether invoked or not.” By the Renaissance, this adage had become a proverb about the inevitability of the divine. Jung adopted it as his personal motto.

At first glance, one could take this as a declaration of conventional religiosity: it is tempting to assume Jung was affirming the Christian God (and by extension that Jungians must be “believers” in the traditional sense). This reading is reinforced by the famous interview near the end of Jung’s life. In 1959, the BBC filmed Jung for Face to Face (interviewed by John Freeman). When asked if he believed in God, Jung paused for a dramatic moment, then answered: “I don’t believe. I know.” The reply has since become iconic. But stopping here would be anathemata to Jung’s legacy. For what Jung meant by “God” was not the omnipotent sky-father of Christian theology. Rather, he was referring to the numinous reality of the psyche itself, i.e. the Self as an autonomous factor, the archetypal dimension that seizes us, whether acknowledged or not.

The Küsnacht inscription is not about creed; it’s about his experience. It spells out a reality on which analytical psychology rests: The numinous does not depend on human recognition for its existence or its efficacy. The archetypal, the divine, the unconscious, all are. They appear in dreams, in bodily symptoms, in synchronistic events, in compulsions, in visions, in altered states of consciousness. Whether invoked or not, they insist upon themselves. The unconscious never remains silent simply because the ego chooses to ignore it.

Yet, as Jung eloquently and prolifically pointed out, there is a qualitative difference between unconscious eruption and conscious invocation of the numinous. Left uncalled, the archetypal often enters life violently. The gods break through as symptoms, overwhelming and disorienting the ego. This is the flood of energy Jung described in cases of psychosis, fanaticism, or collective hysteria during which the archetypal realm takes over, and the person or culture becomes its mouthpiece.

But there is another way. Jung’s opus consistently pointed toward the possibility of meeting the numinous consciously, with reverence. When one calls upon the archetypal realm deliberately, (through ritual, prayer, meditation, active imagination, dream analysis etc.) the relationship between ego and Self shifts. The ego is no longer swept away, but enters into dialogue with what is greater. This reality lies at the core of the religious function of the psyche. To “call” upon the gods is to acknowledge the Other as Other, yet to invite it into conscious life. This attitude is the exact opposite of dogma; it’s about relation. Without respect, the numinous can burn. With respect, it can transform.

The Küsnacht inscription can thus be read as both warning and promise.

Warning: Ignore the unconscious and it will still find you, perhaps destructively.

Promise: Call upon it with reverence, and it comes as guidance and meaning.

This capacity for reverent invocation, Jung exemplified throughout his life and work, can be cultivated. He described it as the symbolic attitude: the disposition to experience life not merely as literal fact, but as an archetypal unfolding. To live symbolically is to notice the resonances between inner and outer, dream and waking, psyche and world. It is this same disposition that allows one to perceive synchronicity, the meaningful coincidence that reveals an ever-present reality for those who have eyes to see. God is present, whether called or uncalled, just as synchronicity is always at work whether noticed or not. Both erupt unconsciously when ignored, but become transformative when approached with symbolic vision.

Jung’s opus was not about ‘belief’ to a dogmatically scripted reality (if it were, he would have most likely answered “yes, I believe”), but about the encounter with the numinous. Yet, it is a religious attitude in the etymological meaning of the word: religare, “to bind back”; to bind consciousness back to the archaic, transpersonal reality of the psyche. The stone words on Jung’s threshold, as on his grave, declare neither creed nor doctrine, but a psychological truth: that God/the gods is/are real and always present. What matters is whether we meet this presence blindly, or with eyes open.